Most people who have used Linux have seen the root directory but not everybody understands what the directories are used for. When a Windows user opens the file manager, everything looks good when they are in their home folder, however, problems start when they explore up the tree looking for the “C Drive” :). For more information about Windows file system structure check out the article on Wikipedia.

Here is a few words for new Linux users coming from Windows. Windows and Linux evolved in very different ways. Once upon a time there was a thing called MS DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System). It was command-line only, but you could still run programs and games. Windows was added later and you could install it on top of DOS. Then you would start up your computer and type in win to start Windows. It used letters to assign drives with A and B being removable disks, since early PCs only had floppy drives. With the addition of hard drives, the letter C became the letter for your internal disk. Additional disks were given the next available letter.

You could install things in DOS wherever you wanted. The windows installed itself in his own directory called “WINDOWS”. Later, Microsoft changed how it booted by evolving their kernel to be less and less dependent on DOS and eventually allowed Windows to boot directly without DOS at all.

Microsoft’s file directory structure kind of stayed the same. Now Linux is different and so is its file structure. It also doesn’t install applications like Windows does. Starting with Windows 95, Microsoft created the “C:Program Files” directory which was the default installation directory for most applications. For the most part Linux follows UNIX traditions which is why it uses the forward slash (/) instead of the back slash () like Windows. Linux also cares about capitalization so you can have things like “some-file.txt” and “Some-File.txt” in the same folder (they are capitalized differently so they are different files). Linux will allow this because they’re technically not named exactly the same.

Mac users who have explored their hard drives might find Linux a little more familiar. This is because Mac’s also evolved from a UNIX ancestor, more specifically BSD. You can read more about different kinds of Linux distros.

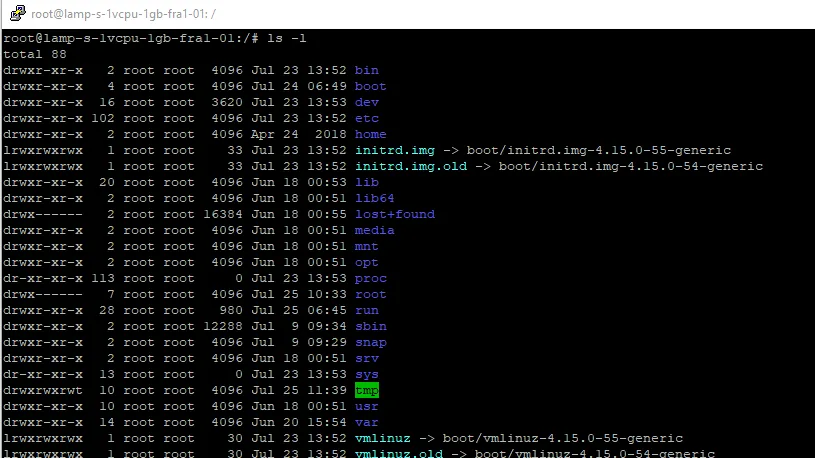

Root (/)

So let’s have a look at the root and go over how all this works. Here we will present the file system folder structure, but if you are interested in general Linux structure, check out the Linux Architecture article.

This layout for the most part is outlined in the FHS (Filesystem Hierarchy Standard) which defines the structure and layout and is maintained by the Linux Foundation. Note that not all distributions follow this and also several ways of structuring the folders has changed over the years but most of what follows still applies in most cases.

/bin and /sbin

Let’s go starting with bin, which is short for binaries. These are the most basic binaries, which is another word for programs or applications. It includes things like ‘ls’ to list your directory, ‘cat’ to display the output of a file, and other. Here we can also point out /sbin, which contains system binaries that a system administrator can use and that a standard user wouldn’t have access to without permission. Both of these folders contain the files that need to be accessible when running in single user mode, as opposed to the usual multi-user mode. Single user mode is a special mode that boots you in as a root user to allow you to do system repairs and upgrades or testing. Networking is usually disabled in this mode because of security issues. When you install a program in Linux it’s typically not placed in these folders.

/boot

/boot is a folder you don’t want to play around. It contains everything your OS needs to boot, in other words your boot loaders live here.

/dev

/dev is where your devices live. Linux again following UNIX has a standard where it was decided that everything is a file. Here you’ll find your hardware. For example, disk would be /dev/sda (or vda if you are in a virtualized environment), and a partition on that disk would be, for example, /dev/sda1, /dev/sda2 and so on. You can also find everything else here, from your webcam to your keyboard. This is typically an area that applications and drivers will access and is rarely something a user should be dabbling in.

/etc

The name of this folder has been argued as standing for “et cetera” or “edit to configure”, as well as others, but it has been confirmed by Dennis Ritchie (creator of Linux) that it did indeed mean “et cetera”. This folder is where all your system wide configurations are stored, such as ‘apt’ configuration, ‘cron’ configuration, Apache configuration, etc. If you’re looking for something that is a system-wide application, this is the place. If you are looking for a per user setting, like for example Libre Office, this would have settings in each user’s folder and it wouldn’t be system-wide because each user can have different settings. This brings us to the next folder which is /home, however I’m going to save this for later.

/lib and /lib64

/lib and /lib64 includes libraries, that is files that applications can use to perform various functions. They’re required by the binaries in /bin and /sbin for example.

/media and /mount

/media and /mnt (mount) is where you would find your other mounted drives such as a floppy disk, USB stick, external hard drive, network drive or even a second hard drive. So if you’re looking for that A, B or D drive this is where you want to be looking. The /media folder wasn’t always around, it was typically just /mnt and that’s where you mounted your storage devices. Nowadays most distros automatically mount devices for you in the media directory. So your USB stick that you inserted would be in media. So why are there two directories? Well if you’re mounting things manually use the /mnt directory and leave the media directory to the OS to manage.

/opt

/opt (optional) is the folder which is usually where manually installed software from vendors resides, though some software packages found in the repo can also find their way here. For example this is where you’ll find a VPN software that you installed, drivers for various printer devices, and also where you can install software you’ve created yourself.

/proc

/proc is where you’ll find pseudo files that contain information about system processes and resources. For example every process will have a directory which contains all kinds of information on that process. The directory names will correspond to the process ID or PID, and each folder will contain a bunch of information about the process. This isn’t something you want to play in, but if you are a developer, if you’re writing applications, this is very handy. Here you can also find information for the CPU for example in file /proc/cpuinfo, and other.

/root

/root is the root user home folder. Unlike a user’s home folder it does not contain the typical directories inside and it does not reside in the home directory. You can store files here if you wish but you need root permissions to access it. The location of this directory also ensures that root always has access to its home folder in case you have the regular users home directory stored on another drive which you cannot access.

/run

/run is fairly new and different distros use it in slightly different ways. It’s a “tempfs” file system which means it runs in RAM. This also means that everything in it is gone when the system’s rebooted or shut down. It’s used for processes that start early in the boot procedure to store runtime information that they use to function.

/snap

/snap is a folder where snap packages are stored and are mainly used by Ubuntu. Snap packages are completely self-contained applications that run differently than regular packages and applications.

/srv

/srv is the service directory where service data is stored. If you run a server such as a web server or FTP server you would store the files that will be accessed by external users here. This allows for better security since it’s at the root of the drive and it also allows you to easily mount this folder from another hard drive.

/sys

/sys which is the system folder and has been around a long time. It’s a way to interact with the kernel. This directory is similar to the /run directory and it’s not physically written to the disk. It’s created every time the system boots up so you wouldn’t store anything here and nothing gets installed here.

/tmp

/tmp is of course a temp or temporary directory. This is where files are temporarily stored by applications that could be used during a session. For example if you’re writing a document in a word processor it will regularly save a temporary copy of what you’re writing here so that if the application crashes it can look here to see if there’s a recent saved copy that you can recover. This folder is usually emptied when you reboot the system. On occasion you might find some files or directory that remain and could be stuck there because the system can’t delete them. This normally isn’t a big deal unless there’s hundreds of files or the files are taking a lot of disk space in which case you might want to log in as the root user in single user mode, navigate to this folder and manually delete them.

/usr

/usr folder is the user application space where applications will be installed that are used by the user. Any applications installed here are considered non-essential for basic system operation. Installed applications will reside in one of several places here such as /usr/bin, /usr/sbin or /usr/local/bin or /usr/local/sbin, with their required libraries stored in /usr/lib or /usr/local/lib. Most programs that are installed from source code will end up in the local folders. Many larger programs will install themselves into /usr/share. Any installed source code such as the kernel source and header files will go into the /usr/src directory.

The /usr directory seems like a confusing mess at first and while the directory structure and what goes where is laid out in the FHS, sometimes you’ll still have to look in other places to find things. Someone making a certain application might not adhere to the standard and could just do what they want. Also some distros may treat these folders differently as well.

/var

/var is the variable directory. It contains files and directories that are expected to grow in size. For example /var/crash holds information about processes that have crashed. /var/log contains log files for both the system and many different applications which will constantly grow in size as you use the system. You’ll also find other things in here like databases for mail and temporary storage for printer queues also known as the spool.

/home

When you enter the /home folder you’ll see that each user has its own folder inside of it. The home folder is where you store your personal files and documents. Each user can only access their own folder unless they use admin permissions. Some users mount the /home folder on a different drive or different partition which allows you to reinstall your system and preserve your files.

The home folder also contains many different directories which store your application settings. These are often hidden (a hidden directory or file is simply one that starts with a period). Linux hides these by default, but you can view them in the file manager by selecting “show hidden files” option or use ‘ls -a” command in terminal.

As you can see Linux is very different from Windows. Although it seems like a mess it’s actually a more efficient way of doing things and allows much more sharing of common resources between packages. When it comes to adding and removing software your distro will have a package manager that will handle all this for you. Package manager tracks where everything is going so that when you remove your package it takes all those files with it.